... filmplus.org/HISTORY

* see Esther's Ras Makonnen 8 part movie

|

* 60,000 Humans (homo sapiens) are limited to Africa and number around 10,000.

Èìïåðàòîðñêàÿ Ýôèîïèÿ * Imperial Ethiopia Medals, Orders -- Spink (images) * 2005 updates : link - e-Hiatory The revolution began with a mutiny of the Territorial Army's Fourth Brigade at Negele in the southern province of Sidamo on January 12, 1974. Soldiers protested poor food and water conditions; led by their noncommissioned officers, they rebelled and took their commanding officer hostage, requesting redress from the emperor. Attempts at reconciliation and a subsequent impasse promoted the spread of the discontent to other units throughout the military, including those stationed in Eritrea. There, the Second Division at Asmera mutinied, imprisoned its commanders, and announced its support for the Negele mutineers. The Signal Corps, in sympathy with the uprising, broadcast information about events to the rest of the military. Moreover, by that time, general discontent had resulted in the rise of resistance throughout Ethiopia. Opposition to increased fuel prices and curriculum changes in the schools, as well as low teachers' salaries and many other grievances, crystalized by the end of February. Teachers, workers, and eventually students--all demanding higher pay and better conditions of work and education--also promoted other causes, such as land reform and famine relief. Finally, the discontented groups demanded a new political system. Riots in the capital and the continued military mutiny eventually led to the resignation of Prime Minister Aklilu. He was replaced on February 28, 1974, by another Shewan aristocrat, Endalkatchew Mekonnen, whose government would last only until July 22. On March 5, the government announced a revision of the 1955 constitution--the prime minister henceforth would be responsible to parliament. The new government probably reflected Haile Selassie's decision to minimize change; the new cabinet, for instance, represented virtually all of Ethiopia's aristocratic families. The conservative constitutional committee appointed on March 21 included no representatives of the groups pressing for change. The new government introduced no substantial reforms (although it granted the military several salary increases). It also postponed unpopular changes in the education system and instituted price rollbacks and controls to check inflation. As a result, the general discontent subsided somewhat by late March. By this time, there were several factions within the military that claimed to speak for all or part of the armed forces. These included the Imperial Bodyguard under the old high command, a group of "radical" junior officers, and a larger number of moderate and radical army and police officers grouped around Colonel Alem Zewd Tessema, commander of an airborne brigade based in Addis Ababa. In late March, Alem Zewd became head of an informal, inter-unit coordinating committee that came to be called the Armed Forces Coordinating Committee (AFCC). Acting with the approval of the new prime minister, Alem Zewd arrested a large number of disgruntled air force officers and in general appeared to support the Endalkatchew government. Such steps, however, did not please many of the junior officers, who wished to pressure the regime into making major political reforms. In early June, a dozen or more of them broke away from the AFCC and requested that every military and police unit send three representatives to Addis Ababa to organize for further action. In late June, a body of men that eventually totaled about 120, none above the rank of major and almost all of whom remained anonymous, organized themselves into a new body called the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army that soon came to be called the Derg (Amharic for "committee" or "council" ). They elected Major Mengistu Haile Mariam chairman and Major Atnafu Abate vice chairman, both outspoken proponents of far-reaching change. This group of men would remain at the forefront of political and military affairs in Ethiopia for the next thirteen years. The identity of the Derg never changed after these initial meetings in 1974. Although its membership declined drastically during the next few years as individual officers were eliminated, no new members were admitted into its ranks, and its deliberations and membership remained almost entirely unknown. At first, the Derg's officers exercised their influence behind the scenes; only later, during the era of the Provisional Military Administrative Council, did its leaders emerge from anonymity and become both the official as well as the de facto governing personnel. Because its members in effect represented the entire military establishment, the Derg could henceforth claim to exercise real power and could mobilize troops on its own, thereby depriving the emperor's government of the ultimate means to govern. Although the Derg professed loyalty to the emperor, it immediately began to arrest members of the aristocracy, military, and government who were closely associated with the emperor and the old order. Colonel Alem Zewd, by now discredited in the eyes of the young radicals, fled. In July the Derg wrung five concessions from the emperor-- the release of all political prisoners, a guarantee of the safe return of exiles, the promulgation and speedy implementation of the new constitution, assurance that parliament would be kept in session to complete the aforementioned task, and assurance that the Derg would be allowed to coordinate closely with the government at all levels of operation. Hereafter, political power and initiative lay with the Derg, which was increasingly influenced by a wide-ranging public debate over the future of the country. The demands made of the emperor were but the first of a series of directives or actions that constituted the "creeping coup" by which the imperial system of government was slowly dismantled. Promoting an agenda for lasting changes going far beyond those proposed since the revolution began in January, the Derg proclaimed Ethiopia Tikdem (Ethiopia First) as its guiding philosophy. It forced out Prime Minister Endalkatchew and replaced him with Mikael Imru, a Shewan aristocrat with a reputation as a liberal. The Derg's agenda rapidly diverged from that of the reformers of the late imperial period. In early August, the revised constitution, which called for a constitutional monarchy, was rejected when it was forwarded for approval. Thereafter, the Derg worked to undermine the authority and legitimacy of the emperor, a policy that enjoyed much public support. The Derg arrested the commander of the Imperial Bodyguard, disbanded the emperor's governing councils, closed the private imperial exchequer, and nationalized the imperial residence and the emperor's other landed and business holdings. By late August, the emperor had been directly accused of covering up the Welo and Tigray famine of the early 1970s that allegedly had killed 100,000 to 200,000 people. After street demonstrations took place urging the emperor's arrest, the Derg formally deposed Haile Selassie on September 12 and imprisoned him. The emperor was too old to resist, and it is doubtful whether he really understood what was happening around him. Three days later, the Armed Forces Coordinating Committee (i.e., the Derg) transformed itself into the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC) under the chairmanship of Lieutenant General Aman Mikael Andom and proclaimed itself the nation's ruling body. *

2007 pages -- 2009 AA

|

History

new -- 2005The most ancient lineage in the world is that of Ethiopia’s Royal family. It is said to be older than that of King George VI by 6130 years. Haile Selassie I, Ruler of Ethiopia, traces his ancestry to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba and beyond that to Cush 6280 B.C.Weep not Ethiopians! thy faith is dead not He Who shall always command thy praise. Those subject to fate cant put end to eternity Nor timelessness fall prey to transient days. Let thine eyes push forth no more floods Like the Nile chaseth forth her waves, Be not decieved by deception's broods Life's enemies, those virulent, insidious knaves Thy King liveth and will ever wear that crown Preordained to grace his thought inspiring head. From David's loins through sage Solomon The sacred scriptures has prophetically said, One would ascend to majestic rule The crowning one be he to occupy the Throne. No ambition's slave or time's fool Is He, so laud you Him and Him alone.Haile SelassieHIM slide-show *Haile Selassie was born Tafari Makonnen in Ethiopia in 1892. He married Wayzaro Menen in 1911, daughter of Emperor Menelik II. By becoming prince (Ras), Tafari became the focus of the Christian majority's approval over Menelik's grandson, Lij Yasu, because of his progressive nature and the latter's unreliable politics. He was named regent and heir to the throne in 1917, but had to wait until the death of the Empress Zauditu to assume full kingship. During the years of 1917-1928, Tafari traveled to such cities as Rome, Paris, and London to become the first Ethiopian ruler to ever go abroad. In November of 1930, Zaubitu died and Tafari was crowned emperor, the 111th emperor in the succession of King Solomon. Upon this occasion he took the name Haile Selassie, meaning "Might of the Trinity." This paper will focus on Selassie's progressive politics and attempts to modernize Ethiopia through technological advances and membership in the world community. Relevant to these topics is Ethiopia's struggle with Italy in World War II, Selassie's embracing of the League of Nations, and his popularity and attention worldwide because of his efforts towards humanitarianism and Ethiopian sovereignty. Ethiopia was a culturally and resourcefully rich land recognized by the European colonial powers as sovereign from as early as 1900. Selassie's predecessor expanded his empire successfully in the 1880's and formed treaties with the Italians, who recognized the imperial potential of northern Africa. Relations became strained, however, in the 1890's when Britain and Italy agreed that Ethiopia should fall under Italian influence. Despite occasional conflicts, Ethiopia under Menelik remained sovereign, and thus we see a stage set for the leadership of Selassie: a free Ethiopia with Italian, British, and French colonies nearby, and an Italian will to expand its territorial claims when its power and opportunity arise. (Marcus, 52)

Well before Selassie's crowning as negus (king), he began work modernizing Ethiopia to rival that which he saw in Europe during his time abroad. He took steps to improve legislation, bureaucracy, government schooling, and health and social services in preparation for his new reign. More importantly in a diplomatic focus, Selassie acted to promote Ethiopian power and sovereignty and secure allies abroad. In 1919 Ethiopia applied for membership into the League of Nations but was banned because its practice of slavery was still strong. By 1923, working with the Empress Zauditu, the slave trade was abolished and Ethiopia was unanimously accepted into the League. He further acted to seek approval of other nations by emancipating existing slaves and their children and created government bureaus to do so. Also prior to his taking of power, Selassie promoted a twenty year treaty of friendship with Italy in 1928 and established legislation in 1930 to ban illegal sales of arms in Ethiopia, and to establish the government's right to procure arms for protection and internal unrest. (Marcus, 60-73)

In 1931, upon assuming power, Selassie established the first Ethiopian constitution, which aimed to re-focus governmental power from many rases to his blood line solely. This move was effective in aiding Ethiopia's modernization through bureaucracy and solidarity, and forced the many regional rases to either oppose him treasonably or join him with their support. (Marcus, 98-100) By 1934, after several suppressed revolts, all the major rases were either supporters or outside the empires influence in the outer regions of Ethiopia. Much of Selassie's loyalty was fostered by the building of schools, universities, and newspapers, as well as increased availability of electricity, telephone, and public health services. The Bank of Ethiopia was also founded in 1931 and introduced Ethiopian currency.

Though the changes in Ethiopia sponsored by Selassie and his new progressive government seemed very promising, there lingered a new threat to the growing country when Benito Mussolini came to power in Italy in 1922. The north African colony of Eritrea, held by the Italians, was harmonious in its African/Italian co-existence from the 1890's until 1922, when Mussolini's administration began to emphasize the superiority of Italian inhabitants, and even enforced the segregation of the population. As late as 1928, motions of peace were made by Italy, but it seemed as though Mussolini wanted Eritrea only as a strategic base for future conquest in Africa. (Marcus, 108) In December 1934, there was an incident seemingly provoked by Italian forces which involved an Ethiopian escort to the Welwel wells used by desert nomads. The League of Nations exonerated both parties in the battle in September 1935, and it seemed to Mussolini that he would not be condemned for his future hostilities. (Marcus, 148-49) Italy invaded Ethiopia one month later without declaring war; the League of Nations condemned Italy as the aggressor, but no actions were taken. The fighting persisted for seven months, and Ethiopia was pushed back quite forcefully. Selassie found his forces unmatched militarily and was shocked at the use of chemical weapons by Italy, and the lack of action taken by the League of Nations. He was forced to exile on May 2 of 1936, a move which raised harsh criticism from many who were used to a warrior emperor of Ethiopia. On June 30, Haile Selassie went to Geneva to seek help from the League of Nations. He made a powerful speech in which he addressed the lack of enforcement of the Italian arms embargo, and quite effectively illustrated the consequences of the League's stifled actions: either there would exist collective security or international lawlessness. (Selassie, Internet) His speech was taken quite emotionally by audiences around the world, especially in America, where he achieved much sympathy. Selassie succeeded in raising the support of the United States and Russia, at least verbally, but Britain and France still recognized the Italian possession of Ethiopia by Italy.

While Selassie was in exile, the Italian forces established new government and attempted to crush the continuing revolts by massacres and segregation. In Britain for most of his exile, he attempted to raise public support for the plight of his country, but gained little attention until Italy entered the war on the side of Germany in June 1940. After the entrance, Britain and Selassie worked together to rally the remaining revolutionary forces in Ethiopia. He proceeded to Khartoum in 1940 to be in closer contact with his troops and British coordinators. With an army of British, South African, African, and Ethiopian soldiers, Haile Selassie re-entered Addis Ababa on May 5, 1941, but fighting continued on Ethiopian soil until January 1942. During the years of war, Selassie controlled internal affairs, but with required British approval. Upon his return he, without consulting Britain, appointed a seven member cabinet and a governor of Addis Ababa. The British aided Ethiopia in training a new army with advisers, which helped him substitute experienced administrators in place of traditional nobility, but he rejected British help whenever the reforms threatened his own personal control over his country. His stubbornness and foresight to retaining power showed Selassie to be a determined dictator, but certainly not without Ethiopia's benefit in mind. The modernization's made by Britain concerning currency, industrialization, and bureaucracy made Selassie see the major importance in modernizing in order to survive. He attempted to secure Eritrea as Ethiopian, but the decades of Italian influence imparted an independent sense on the part of the Eritreans, and the British denied his wishes.

When Selassie returned to power, he realized the necessity of a dependable tax base and issued a flat tax based on the richness of the land. Unfortunately, the nobles of several provinces battled the tax and the path was lain for opposition to the newly re-established government. Selassie backed down from his new tax brackets and issued a flat tithe to all noble landowners who resisted, but this merely passed the tax on to the tenants of the regions, who carried the entire burden of taxation. Another huge reform made by Selassie was the 1948 change in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. He removed the responsibility of appointment of the Church's patriarch from Alexandria to himself, a move which revolutionized the sixteen century old tradition.

After World War II, Selassie saw himself as a humble, but emerging, world leader. (Prouty, 93) Ethiopia was a founding member of the United Nations and the Organization of African Unity. Haile Selassie, after his aid from Britain wound down in 1953, sought and developed an aid-based relationship with the United States, and later sought and received aid from such diversified nations as Italy, China, West Germany, Taiwan, Yugoslavia, Sweden, and the Soviet Union.

Within his country, Selassie favored political realism, and attempted to make peace with the many Ethiopian factions- ethnic, religious, and economic- through appeasement and compromise. Despite his growing international stature, however, his internal influence lacked major support which would, in the future, lead to problems in his stability as a ruler. The emperor attempted to further strengthen the national government by placing newly educated ministers with more specific powers, establishing a central judiciary and self-appointing its judges. He also proclaimed a new national constitution in 1955. The constitution was enforced by a new, younger, foreign-educated staff, who sympathized with Selassie's reforms and were intellectually supportive of his claims. It was also heavily influenced by Selassie's concern for international image, as many African countries were thriving under colonial support and Ethiopia was still laying its claim to Eritrea. (Prouty, 93) The new constitution emphasized Selassie's religious right to power, and while it promised several inherently American rights (freedom of speech, assembly, and due process), the Ethiopian population lacked the literacy and independence from local nobility to really appreciate its declarations.

Selassie's major changes in form of the Ethiopian government promised huge reforms, and when these were realized to be slowly obtained, a coup d'état occurred in Addis Ababa in December 1960, while Selassie was abroad on one of his frequent diplomatic missions. (Prouty, 40) While initially successful, the coup led by the Imperial Bodyguard, police chief, and intellectual radicals lacked the public support necessary, and fell upon the return of the emperor and his assertion of the loyalty of the army and air force, as well as the church. The coup's failure did, however lead to the polarization of the traditional and progressive factions, and the public awareness of the need to improve the economic, social, and political position of the population.

After the coup, Selassie tried to calm his opponents mostly through land grants to officials, but with little social or political reform. In 1966, a plan to reform the tax system with intent to destroy the landowners grasp on the economy was drafted, but opposed vigorously by the parliament, who were all landowners. The years prior to 1974 were filled with rising inflation, corruption, and famine, as well as growing discontent by many of the organized urban groups and unions. Selassie had organized his military so that each branch opposed each other in class, benefits, or treatment in order to keep one from becoming so powerful as to threaten his power. It was perceived that the droughts and famines within the army and the public were intentional, and that civil freedoms were increasingly disappearing. Mutiny in the army branch of the military began on January 12, 1974, and was followed by several provincial takeovers in February. In early June, a group of about 120 military officers formed a group known as the Derg (committee) who represented the military and worked behind closed doors to gain power militarily. Although they claimed allegiance to the emperor, they began arresting aristocracy and parliament members who were associated with the old order. This group effectively removed Selassie's means of governing, as they had complete military control. In July 1974, the Derg demanded a new constitution; when it was found to be unsatisfactory to their "Ethiopia First" ideology, they proceeded to undermine the emperor's authority, and enjoyed much public support. (Tareke, 204-13) The emperor's estate and palace were nationalized and in August, Selassie was directly accused of covering up famine of the early 1970's which killed hundreds of thousands of people. On September 12th, he was formally deposed and arrested and power was given to the Derg, formally renamed the Provisional Military Administrative Council. In August 1975, His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie died under questionable circumstances under house arrest, and was secretly buried. (Prouty, 93) His early legacy of Ethiopian pride and sovereignty, had transformed itself to a major struggle of the old versus the new orders. The old order was effectively destroyed by 1977, and the Derg began its new agenda of socialism in the Ethiopian government.

Works Cited:

1. Marcus, Harold G. Haile Selassie I: The Formative Years, 1892-1936. Los Angeles: UC Press, 1987.

2. Prouty, Chris, and Eugene Rosenfield. Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. London: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1982.

3. Tareke, Gebru. Ethiopia: Power and Protest. Cambridge UP.

4. Haile Selassie's Appeal to the League of Nations. Internet address: http://www.boomshaka.com/league.html. 29 April 1996.This paper was written May 1, 1996, by Mike Cutri (acutri@acusd.edu)

New Way of Lifehttp://www.hrono.ru/land/1900efio.html -- Ýôèîïèÿ 20 âåê ïî-ðóññêè

November 2, 1966What we seek is a new and a different way of life. We search for a way of life in which all men will be treated as responsible human beings, able to participate fully in the political affairs of their government; a way of life in which ignorance and poverty, if not abolished, are at least the exception and are actively combatted; a way of life in which the blessings and benefits of the modern world can be enjoyed by all without the total sacrifice of all that was good and beneficial in the old Ethiopia. We are from and of the people, and our desires derive from and are theirs.

Can this be achieved from one dusk to the next dawn, by the waving of a magic wand, by slogans or by Imperial declaration? Can this be imposed on our people, or be achieved solely by legislation? We believe not. All that we can do is provide a means for the development of procedures which, if all goes well, will enable an increasing measure and degree of what we seek for our nation to be accomplished. Those who will honestly and objectively view the past history of this nation cannot but be impressed by what has already been realised during their lifetime, as well as be awed by the magnitude of the problems which still remain. Annually, on this day, we renew our vow to labour, without thought of self, for so long as Almighty God shall spare us, in the service of our people and our nation, in seeking the solutions to these problems. We call upon each of you and upon each Ethiopian to do likewise......

Above all, Ethiopia is dedicated to the principle of the equality of all men, irrespective of differences of race, colour or creed.

As we do not practice or permit discrimination within our nation, so we oppose it wherever it is found.

As we guarantee to each the right to worship as he chooses, so we denounce the policy which sets man against man on issues of religion.

As we extend the hand of universal brotherhood to all, without regard to race or colour, so we condemn any social or political order which distinguishes among God's children on this most specious of grounds.

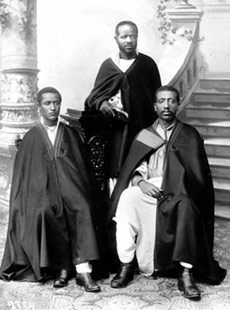

Having just arrived in Ethiopia, Leontyev saw that the Ethiopian people wished to be on friendly terms with the Russians. In 1898, after having familiarized himself with Leontyev's travel notes, a literary man by the name of Yelets, from St. Petersburg mentioned, "The travellers were given a hearty welcome in Harer by Ras-Mekonnen. That was the Ethiopian emperor's injunction. Five miles from the city, Leontyev and his companions were met by a colossal procession headed by the priesthood bearing standards. There were crowds of people. On both sides of the road to Harer Ethiopian troops were kneeling. The Russian expedition immediately gained the general sympathy of the Ethiopian authorities and common people. The reception in Entoto was even better than in Harer. The attentiveness, kindness and hospitality of the Ethiopians was really surprising." *

Having just arrived in Ethiopia, Leontyev saw that the Ethiopian people wished to be on friendly terms with the Russians. In 1898, after having familiarized himself with Leontyev's travel notes, a literary man by the name of Yelets, from St. Petersburg mentioned, "The travellers were given a hearty welcome in Harer by Ras-Mekonnen. That was the Ethiopian emperor's injunction. Five miles from the city, Leontyev and his companions were met by a colossal procession headed by the priesthood bearing standards. There were crowds of people. On both sides of the road to Harer Ethiopian troops were kneeling. The Russian expedition immediately gained the general sympathy of the Ethiopian authorities and common people. The reception in Entoto was even better than in Harer. The attentiveness, kindness and hospitality of the Ethiopians was really surprising." *

photo: Saint-Petersburg. Extraordinary Ethiopian delegation in St. Petersburg. In the photograph: Prince Belyakio (right), Prince Damto (left), Ato-Iosiph, personal secretary to Menelik II (centre). 1895. Photo by Anufriyev.

* Ras Makonnen in London 1902 [ dead link ]

Ethiopian Heroes